Element 6 – Cultivar

It should seem obvious that the genetics of a tea bush have significant contributions to the final character of a tea, however, identifying bush’s cultivar (or lack thereof) is rare in the sales of tea. The influence of tea bush genetics is so underplayed that there is even the erroneous idea that floats around the tea industry that one can make any style of tea from any cultivar.

Perhaps the reason tea bush cultivars are not discussed in the marketing of tea is that exactly how specific cultivars are used for making particular teas can be very confusing. For example, a tea maker may use pluckings from two different cultivars grown on the same farm to make a single lot of tea. One may be an heirloom plant, and the other a hybrid developed for high and early yields. Still, the name (and price) of the finished tea from these two cultivars would not be distinct and the impression that some buyers might have is that they are getting a batch of tea made entirely of an heirloom variety from the region, when in fact they are not.

A specific example of this confusion is the popular Chinese wulong tea, Tie Guan Yin. This tea’s original cultivar is in fact named “Tie Guan Yin” and this original Tie Guan Yin cultivar is slow to yield. A true Tie Guan Yin bush might have to grow for four or five years before it can be harvested. There are three other common cultivars in the region that grow and yield much quicker, although the character of their finished tea is quite different — richer in aroma but lacking Tie Guan Yin’s distinctive aftertaste. Despite this, the made tea from these three other cultivars almost always marketed as Tie Guan Yin to leverage the name recognition of the region’s most famous tea. It makes little difference that some find these non-traditional cultivars to be more to their taste.  The point is, a tea drinker has only a foggy idea of what they are actually buying if a tea is merely labeled “Tie Guan Yin” and the bush varieties used in its production are not disclosed.

The point is, a tea drinker has only a foggy idea of what they are actually buying if a tea is merely labeled “Tie Guan Yin” and the bush varieties used in its production are not disclosed.

The bottom line in all of these elements is that if you don’t know what a tea is, you don’t know its value. The market will establish the price – perhaps a Longjing 43 will draw the best price over time. But if you don’t know the cultivar you don’t know what kind of Longjing you have. Having a tea’s market name alone cannot establish its value.

Even if a single variety is not used, say in the case of tea grown from seed or blends coming from different cultivars being grown in the same garden, disclosing this information is still vital.

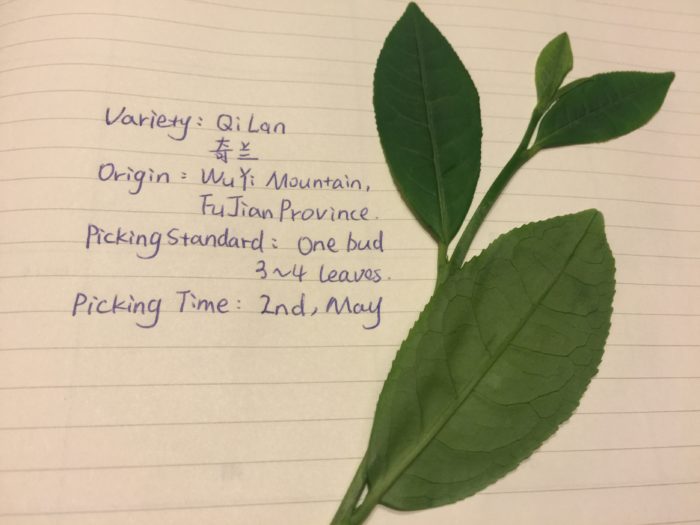

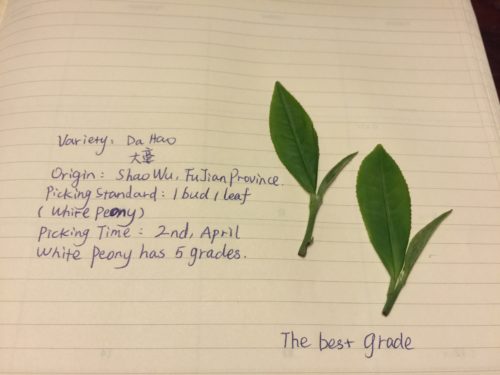

Cultivar labeling is already foundational in the marketing of other specialty foods – grapes for wine, beans for coffee, hops for craft beer. Indeed, the value of many teas are already tied to their creation from a certain variety or from seedlings. For example, Wuyi Yancha Wulong teas are now commonly named for their variety. The reasoning holds throughout these instances that plant biology has significant influence on the final character of a product.